This is one wrong way to design a FORTRAN to C++ interface.

But let's start at the beginning. From FORTRAN callable C++ function must be declared with extern "C" to disable name mangling.

The function funcCPP expect a 2D array. Two items a 3 values. Calculate the sum and return it.

Rember: C counts from 0 and the right most index is the fastest index.

#ifdef __cplusplus

extern "C" {

#endif

double funcCPP(double arr[2][3]);

#ifdef __cplusplus

}

#endif

double funcCPP(double arr[2][3]) {

return arr[0][0] + arr[0][1] + arr[0][2] + arr[1][0] + arr[1][1] + arr[1][2];

}

The generated ASM code (GCC -O1) looks straight forward. Almost perfect (except of SIMD). Nothing more to say.

funcCPP:

movsd (%rdi), %xmm0

addsd 8(%rdi), %xmm0

addsd 16(%rdi), %xmm0

addsd 24(%rdi), %xmm0

addsd 32(%rdi), %xmm0

addsd 40(%rdi), %xmm0

ret

Now we implement an FORTRAN interface for that function. Using iso_c_binding module to make life easier. But the compiler didn't to any real check. If you add an parameter in the C function and forget to add it in the FORTRAN interface -> BOOM.

The array is pass as an 1D array.

module CPPinterface_m

use, intrinsic :: iso_c_binding

implicit none

interface

function funcCPP(arr) bind(c, name="funcCPP")

use, intrinsic :: iso_c_binding

implicit none

real(c_double), dimension(*) :: arr

real(c_double) :: funcCPP

end function

end interface

end module

The main code is a subroutine func which get an 2D array with N items a 3 values. The variable idx contains the position of the items we are interested in. This values are passed to funcCPP. But the two items at position idx(1) and idx(2) are not consecutive stored in RAM. So the compiler has to generate code which make a copy of the six floating point values. That's not what we intend to.

module prog_m

use CPPinterface_m

implicit none

integer :: N

contains

subroutine func(arr, idx)

implicit none

real(8), intent(inout) :: arr(3,N)

integer, intent(in) :: idx(2)

real(8) :: res

res = funcCPP(arr(:,idx))

end subroutine

end module

You can see it right here in the assembler code. I commented it for you. The data is passed through stack.

__unrunoff_m_MOD_func:

subq $56, %rsp # allocate 56 bytes on stack

movslq (%rsi), %rax

leaq (%rax,%rax,2), %rax # calculate address of first item

leaq (%rdi,%rax,8), %rax

movsd -24(%rax), %xmm0 # copy arr[0][0]

movsd %xmm0, (%rsp)

movsd -16(%rax), %xmm0 # copy arr[0][1]

movsd %xmm0, 8(%rsp)

movsd -8(%rax), %xmm0 # copy arr[0][2]

movsd %xmm0, 16(%rsp)

movslq 4(%rsi), %rax

leaq (%rax,%rax,2), %rax # calculate address of second item

leaq (%rdi,%rax,8), %rax

movsd -24(%rax), %xmm0 # copy arr[1][0]

movsd %xmm0, 24(%rsp)

movsd -16(%rax), %xmm0 # copy arr[1][1]

movsd %xmm0, 32(%rsp)

movsd -8(%rax), %xmm0 # copy arr[1][2]

movsd %xmm0, 40(%rsp)

movq %rsp, %rdi

call funcCPP@PLT # call the C++ function

addq $56, %rsp # release stack space

ret

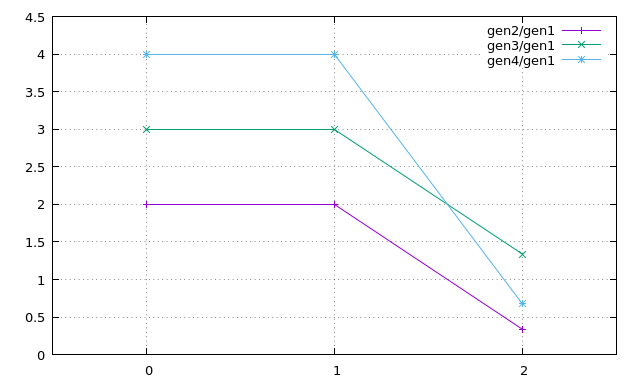

We have 6 ASM instruction to process the data and 21 instructions to access the data. Nope. Fail.